Every month or two I transfer data from my GR to my PC. My memory of what I took during that time is almost gone by then. I check the data I just backed up and try to fill in the blanks, thinking, “Oh, this is what I did this month.” Although I think of myself as taking a lot of everyday scenes and snapshots, when I look at the actual photos I take, I find that some months have a large number of landscape photos. I used to take a lot of landscape photos. Especially when I was in school, I liked the tonality of the images on photographic paper and the prints themselves more than the photographic images.

At that time, Mr. Eikoh Hosoe was teaching at the Photography Department of Tokyo Polytechnic University, where I was a student. In his “Photographic Art Studies" class, he would always bring original prints by various artists and give us explanations about them. I vividly remember one day in class when he brought an old photograph of a landscape. “This is the oldest photograph I own,” he said, showing us a print that was so faded that it looked as if the image might disappear at any moment, hovering vaguely in the dimly lit classroom. He smiled and said, “Well, boys, now you know how beautiful photographs can be.”

Since that day, I have dedicated myself to making “beautiful prints”. Mr. Hosoe's extraordinary passion and obsession for photography was backed by his solid philosophy, technique, knowledge, and experience. Up to that point, I had thought that it was enough just to look at his photographs. The more I listened to him, the more I thought there was no point in me doing photography. However, I found a goal, or rather a light, that I could approach a little: to make prints. Let's just try to make beautiful prints with excellent tonality, I said to myself. I thought that if I did that, I might be able to see the next light.

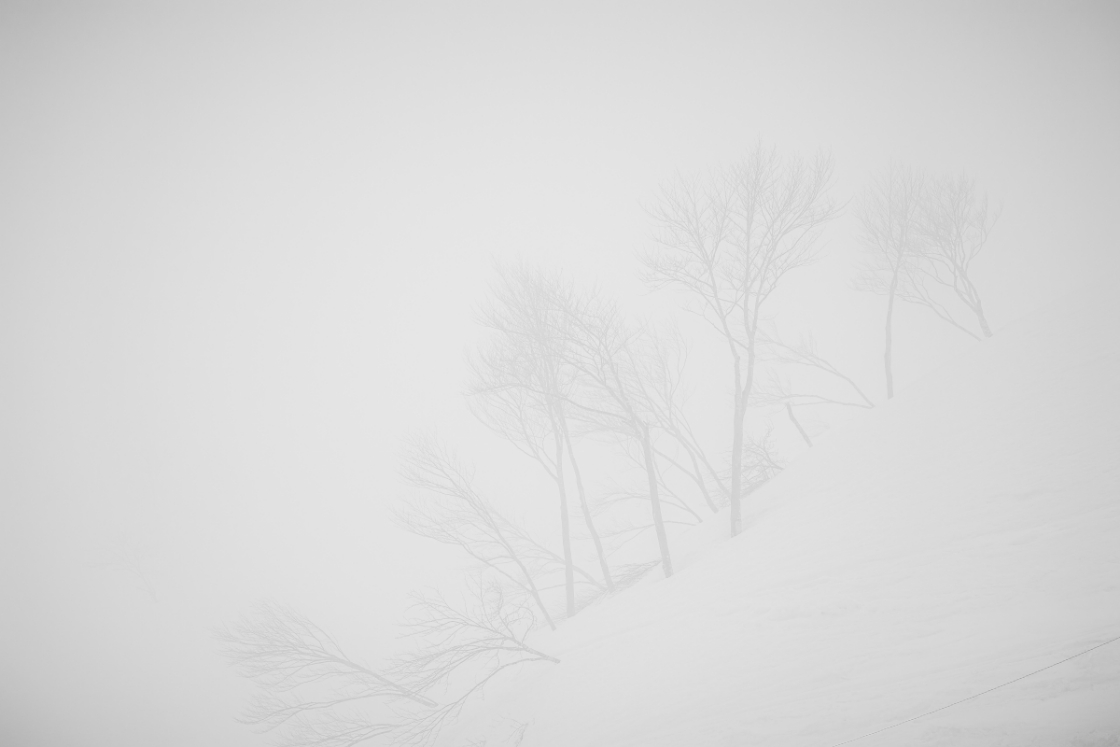

Since the goal was to make prints, any subject that was suitable for that purpose would be fine. One of my role models, of course, was the landscape photography of Ansel Adams, so I took landscape photographs myself. As I repeated the process of shooting, developing, and printing the negatives, I began to understand why mountainsides and driftwood on the beach lit by front light, and soft landscapes covered with snow and fog, all had good tonal gradations. From that point on, I gradually began to search for subjects in my own way. I began to pay attention to light and texture when taking portraits and snapshots.

Because of that one photo he showed us, a photo that almost disappeared, I am still fascinated by photography, and I continue to create and study it. I would like to think that I have come a little closer to him, just in terms of my passion for photography.

This year (2024), on September 16, Mr. Eikoh Hosoe passed away. As one of his many descendants, I would like to pass on something I inherited from him to students who aspire to become photographers. I would like to express my deepest gratitude for the kindness he showed me during his lifetime.

Ryo Ohwada

Born 1978 in Sendai, Japan. Graduated from Tokyo Polytechnic University, Department of Photography, and completed the Graduate Course in Media Art at the same university. In 2005, he was selected as one of the "ReGeneration.50 Photographers of Tomorrow" by the Kunstmuseum Elysee, Switzerland. In 2011, he received the New Photographer Award from the Photographic Society of Japan. He is the author of "prism" (2007, Seigensha), "Gohyaku rakan (Five Hundred Arhats)" (2020, Ten'onzan Gohyaku Rakanji Temple), "Journal during COVID-19 State of Emergency" (2021, kesa publishing), "Shashin seisakusha no tame no shashingijutsu no kiso to jissen (The Basics and Practice of Photography Technology for Photographers)" (2022, Impress), and with poet Chris Mozdel, "Behind the Mask" (2023/Slogan), etc. Associate Professor at the Faculty of Arts, Tokyo Polytechnic University.

www.ryoohwada.com

https://www.instagram.com